Review of Children of the Wind and Water

The Air current in the Willows is one of the near famous English language children'south books, one of the most famous books about animals, and a archetype volume about "messing virtually in boats." Famous, it certainly is. Although it has never been quite the international icon that Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has become, Kenneth Grahame's eccentric masterpiece tin exist read in Afrikaans as Die Wind in die Wilgers, in Italian as Il Vento nei Salici, in Finnish as Kaislikossa suhisee, in Portuguese as As Aventuras de Senhor Sapo and in dozens of other languages. It is currently available in well over 50 editions in English language: there are versions in verse, graded readers for learning English language as a strange language, audio and video adaptations, plays (notably by A.A. Milne and Alan Bennett), films, picture books (with or without stickers), pop-up books, knitting patterns, graphic novels and scholarly annotated editions. At that place are sequels, such as William Horwood's The Willows in Winter (1993), gospel meditations, a cookery book and Robert de Board's Counselling for Toads (1998), an introduction to psychotherapy. E.H. Shepard's illustrations accept been used on national postage stamps and to advertise England itself in the 1980s English Tourist Lath serial, "Making a Intermission for the Real England." The book has been the inspiration for a sculpture trail, one of the well-nigh successful rides in Disneyland and a musical adaptation (by Julian Fellowes) in 2016, which was the first London West End musical to raise £1 million through crowdfunding. What makes all this mysterious (autonomously from the fact that this quintessentially English book was written past a Scot) is that The Wind in the Willows is not a children's volume at all—neither the author nor the original publishers ever suggested that it was. Nor is it an creature story: the characters are, every bit one of the original reviewers, the novelist Arnold Bennett, observed, "meant to exist nothing only human beings," or as Margaret Blount in her book on animals in fiction, Brute Land, put information technology, "for animals, read chaps." And boats appear substantially in only ii of the 12 capacity. Even the title is mysterious—the word "willows" never appears in the book: Grahame's original suggestion for a title was Mr. Mole and his Mates.Scots Observer.

"W.E. Henley's Young Men," writing short essays for the Scots Observer.

Merely, surely, information technology is a book about small and non so small animals—a Toad, a Rat, a Mole and a Badger (and therefore this must exist a children'southward book). If so, then these are animals who potable and smoke, ain houses, bulldoze (and steal) cars, row boats, escape from jail, yearn for gastronomic nights in Italian republic, swallow ham and eggs for breakfast and write poetry—while Toad combs his hair, and the Mole has a black velvet smoking-jacket.

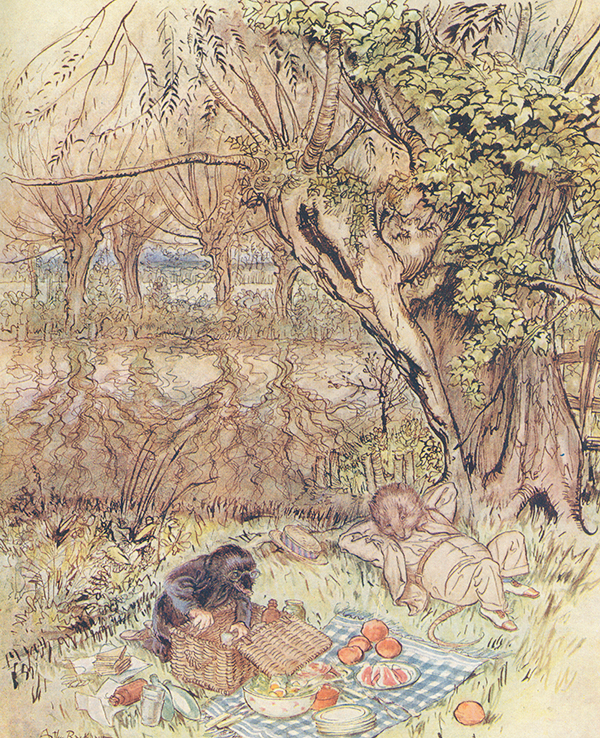

Of form, very occasionally they acquit like animals. Mr. Mole, in the midst of thoroughly human spring-cleaning, briefly turns into a mole, scrabbling and scrooging his way to the surface; the aristocratic Otter, languidly enjoying a riverbank picnic (which includes cold tongue, pickled gherkins and lemonade) suddenly turns into an otter and swallows a passing mayfly.

But for the nigh office, the book is about a group of well-off, leisured English gentlemen. Even more importantly, the book hardly ever addresses itself to an audition of children: as Humphrey Carpenter put it, "The Wind in the Willows has nix to do with childhood or children, except that it can be enjoyed by the immature."

"These are animals who beverage and smoke, own houses, bulldoze (and steal) cars, row boats, escape from jail, yearn for gastronomic nights in Italy, swallow ham and eggs for breakfast and write verse."Of course, it begins—and began—as a children's volume. Like other famous children's books—such every bit Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,The Hobbit and Treasure Isle—it started life as a story for a particular child, and this shows most in the opening chapter. Like all these books, The Wind in the Willows grew in the writing and ended upwards as something quite different from, and something much more than complex than, a bedtime story. But whereas Alice'due south Adventures is a children's volume that tin be read by adults, The Wind in the Willows is an adult's book that tin be read by children. This is because (and this also accounts for its relative lack of international success) its landscapes and cultural references are securely embedded in Edwardian England—whereas Alice moves in a detached world of fantasy, and the many period references in that volume are subconscious in the background.

Into which genre does it fit? The respond to that is that Grahame ruthlessly borrowed from and played with the major pop genres of his day: the river book, the caravanning volume, the motoring thriller, the rural idyll (consummate with Christmas carol), the pseudo-mystic "spiritual" writing of the "decadents" (complete with miasmic pagan verse) and, of course, the rollicking boys' run a risk story. And he cheerfully parodies George Borrow, W.S. Gilbert, and Sherlock Holmes, caricatures his friends, and celebrates his own delights and frustrations.

"In that location's common cold craven . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscress

"In that location's common cold craven . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscresssandwidgespottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater—"

Arthur Rackham'due south 1939 view of the iconic picnic.

One of the mystifying things for those who would effort to make The Wind in the Willows into a children's book is its attitude to adventure. Anything likely to disturb its cozy world is ruthlessly suppressed—the Mole stops the Rat from heading to the warm south in "Wayfarers All"; Toad's rebellion is crushed by all his "friends"—and the Mole'south initial, childlike curiosity most the globe is put firmly in its place in the very first chapter. As he and Rat row along the peaceful river, the Mole looks into the distance:

"And beyond the Wild Woods again?" he asked; "where information technology's all blue and dim, and one sees what may be hills or perhaps they mayn't, and something similar the smoke of towns, or is it only cloud-migrate?"

"Across the Wild Wood comes the Broad Earth," said the Rat. "And that'southward something that doesn't affair, either to yous or me. I've never been at that place, and I'one thousand never going, nor you either, if you lot've got any sense at all. Don't e'er refer to it again, please. Now then! Here's our backwater at last, where nosotros're going to dejeuner."

This certainly concurs with the romantic idea that children'due south books should be safe, and the Edwardian period has been portrayed—especially in children's literature—as peaceful and retreatist. In fact, it was a period of political and cultural instability, change and fear. Rumors of war—especially, although non exclusively, with Germany—were common; the German boxing-armada was expanding; the Boer wars had shaken United kingdom's religion in its ground forces. No wonder the Water Rat is no fan of the Broad World.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from The Making of The Wind in the Willows by Peter Hunt, published by Bodleian Library Publishing. © 2018 past Bodleian Library Publishing. All rights reserved. Images copyright © Bodleian Library, Academy of Oxford.

Source: https://lithub.com/the-wind-in-the-willows-isnt-really-a-childrens-book/